The school experience for young people is always evolving – a reality perhaps more obvious than ever in recent months, as students nationwide have turned to virtual or at-home learning in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. But for LGBTQ young people, life at school has changed in recent decades dramatically as classmates, teachers, and administrators open their hearts and minds to the unique challenges that LGBTQ students grapple with.

The school experience for young people is always evolving – a reality perhaps more obvious than ever in recent months, as students nationwide have turned to virtual or at-home learning in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. But for LGBTQ young people, life at school has changed in recent decades dramatically as classmates, teachers, and administrators open their hearts and minds to the unique challenges that LGBTQ students grapple with.

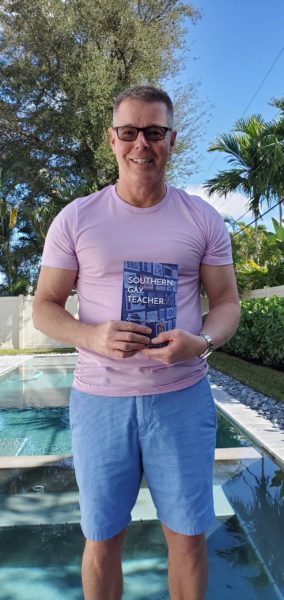

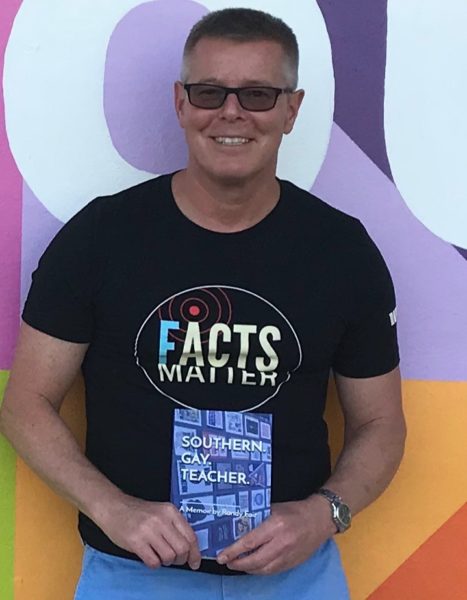

For more than 30 years, Randy Fair had a front-row seat to the changing nature of the educational environment for LGBTQ students, and now, in his new book Southern. Gay. Teacher., published February 1 by Atmosphere Press, he writes about his experiences as a gay teacher working with students, parents, and teachers.

The Campaign for Southern Equality caught up with Randy Fair, who lives in Wilton Manors, FL, to interview him about Southern. Gay. Teacher. And what he wants readers to get out of his memoir. Learn more about the book, which you can buy online here or on Amazon here.

AP: Tell us a bit about yourself and the book!

RANDY FAIR: I taught in the Atlanta area for 31 years, and so what I’m trying to do in the book is tell some of these stories that happened over the 31-year period, showing not only how times have changed but also identifying what’s wrong with the school system.For example, in the early 90s, I taught a class that was called Senior Non-College Bound English. It was really a rough class. One kid was just very mild-mannered, and two weeks before graduation, in class, he said, “I hate fa**ots.” And I told him not to say that, but he came in the next day and said it again, and I took him in the hallway and reminded him again not to say it. The third day, he said the same thing. So I sent him to the administration. Later, I asked him what happened in the administrative office, and he said, “They laughed.”

The next day, I assigned him detention with me, and while I thought he maybe wouldn’t show up, he did – and he actually showed up early. We sat there in silence, and he said, “You know why I hate fa**ots? You wanna know why I hate so-called gay people? My father is a so-called gay person. And he ran away with his boyfriend and left my mom, and I haven’t seen him my whole life, and now he wants to come to our graduation.” I realized that he wanted to call the gay teacher a cruel name because he wanted help understanding why his father did this to him; he thought a gay man could give him that help.

That’s why I think the straight kids need to hear stories like these just as much. My book collects stories like that, and my hope is that they show how there’s an impact for LGBTQ kids and straight kids to have different learning experiences, including being taught by a teacher who is gay.

AP: Definitely. Can you give us a taste of any other stories featuring in the book?

RF: One story is about he first time I had a transgender student, and it helped me realize how some of the things I’d been doing were probably detrimental to the transgender student without me even realizing it. In the 80s and 90s there weren’t so many examples in pop culture or in the education field more generally about how to be inclusive to all students, and so we sort of had to learn while on the job.

RF: One story is about he first time I had a transgender student, and it helped me realize how some of the things I’d been doing were probably detrimental to the transgender student without me even realizing it. In the 80s and 90s there weren’t so many examples in pop culture or in the education field more generally about how to be inclusive to all students, and so we sort of had to learn while on the job.

I had one student, for example, who was born female but identified as male. When the kids came in the classroom, I would always say, “Welcome sir,” or “Welcome madam.” I said to this student, “Welcome, sir,” because he seemed more comfortable identifying that way – but when we played games in class, I usually divided the teams up by gender. The theory at the time was that pitting the boys against the girls forced the girls to choose a girl as team leader – since when I had had them pick teams before, they always picked a boy to lead. But when I had this student, I realized that he didn’t want to be on the girls’ team because he’s not a girl, and he didn’t want to be on the boys’ team because they would ostracize him.

One day, the administration outed the student by saying “Can you send her to the office” over the intercom, and so, in alignment with the student’s wishes, I asked the administration to refer to him as male. They said, we don’t want to get sued, they’re legally female, etc. They just wanted to ignore the issue.

The book is full of those kinds of stories that we need to have as educators. I used to speak at Georgia State to the classes that were preparing to become teachers, and most of them had never thought about these issues that were coming up in the classroom.

I taught in the Atlanta area for 31 years, and so what I’m trying to do in the book is tell some of these stories that happened over the 31-year period, showing not only how times have changed but also identifying what’s wrong with the school system.” – Randy Fair

AP: What are some of your biggest personal reflections about 31 years as a teacher? And what do you look back on now?

RF: I think If there’s one regret I have, it’s that I wish I had spoken out even more. I feel like a lot of LGBTQ teachers are silenced right now because they’re fearing for their jobs, especially in these states where anti-LGBTQ laws exist. I felt silenced back then in Georgia, and I can’t imagine what a teacher in Texas or Alabama feels like. Both states have anti-LGBTQ curriculum laws prohibiting open discussion of LGBTQ people.

Now that I’m retired, there’s nothing they can do to me, it’s the perfect time for me to bring these issues up and speak up for these teachers who too often can’t speak up now.

AP: What’s the biggest message you want people to take away from reading your book?

RF: The biggest message that I want the book to deliver is that I want people to start thinking about the ways that we treat LGBTQ students, parents, and teachers. My teachers in school inadvertently helped me come to terms with the fact that I was a gay man; we were in Alabama, and while a lot of people weren’t accepting of this, some of my teachers were accepting.

I don’t want to see LGBTQ teachers having to silence themselves. It’s like teaching with the metaphorical one arm behind their back. Heterosexual teachers use a lot of metaphors from their own family experiences, they put family pictures on their desk, they relate to kids in a very personal way. I tell one story in the book about a straight teacher. I was doing my dissertation, and I was observing a teacher doing a grammar lesson. The teacher kept making specific references to heterosexuality, discussing family life, boyfriends, girlfriends, and more. At one point she described subjects and verbs, saying, “They work as a team. Just like my husband and I, we work as a team.” Those examples weren’t seen as political or risky – but if an LGBTQ teacher did that, people would say, ‘Why are you being so political and controversial?’

There’s sort of a double standard there. Sometimes LGBTQ teachers have to be more cautious because of their fear of losing their job. That makes it harder for them to be a good teacher when you’ve cut off this whole slice of their life. Those are some of the types of stories I’m hoping to raise with the book.

Gay. Southern. Teacher has been featured in The Atlanta Journal Constitution, The Georgia Voice, and more. Learn more about the book, which you can buy online here or on Amazon here.